Empowering Students With Design Thinking

During a two-week design thinking project, middle-school students drew on their empathy for homeless people to design and build a prototype interim housing unit from shipping pallets.

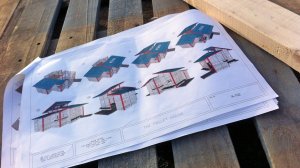

It's a cold January school day in South Carolina, and while temperatures hover in the thirties, the stiff breeze makes it feel like it's in the teens. Despite these conditions, the bundled-up middle school students press on with their assigned tasks: this group is moving pallets, that group is hammering them in place. Another carefully studies the blueprints of the tiny, 250-square-foot house being built, using what they've recently learned in math class to determine the angle of cuts for the lumber, and then passing along instructions about where the boards should be placed.

As I assist some students with holding up a heavy section of pallet-constructed wall, I glance over at Luca, a seventh-grade boy whose eyes are filled with wonder. "Never in my life did I think that I'd be building a house, Mr. Riddle, especially one that can be used to help the homeless. And we're just kids! This is amazing!"

Working outside in this frigid weather is tough. Yet the students are inspired to complete the project because they've developed newfound empathy for the homeless in our community, and working in these conditions deepens that understanding -- especially when they think of those who slept outside the night before in a makeshift camp only a few miles from the school.

Instead of sitting in a classroom and learning from a textbook, these sixth- to eighth-grade students have been empowered to apply their studies in an authentic way. The SFCSxDesign Pallet House Project is only one example of a growing number of educational initiatives nationwide that encourage students to tackle real-world challenges through utilizing the design thinking process.

Establishing a Mindset

Design thinking is a human-centered approach to problem solving that begins with developing empathy for those facing a particular challenge. In schools, it can serve as a framework for providing students with meaningful work that allows them to grow in their ability to define problems, empathize with others, create prototypes of their ideas, and hone those prototypes through multiple iterations until they have generated a viable solution to the challenge at hand. Design thinking encourages students to have a bias toward action (don't wait until you're older to make a difference; do it now!) and because of its reliance on rapid prototyping, frees them to embrace the notion of failing forward (it's OK to make mistakes; that's how we learn).

While there is a specific process that design thinking follows, perhaps its greatest impact on our students has not been in learning the methodology itself but in the establishment of a mindset that promotes an understanding of others.

As a growing number of schools adopt project-based or problem-based learning, some fail to realize that students become effective problem solvers only when given meaningful, relevant, problems to solve. We may say that we want students to apply their knowledge and skills in innovative new ways, yet too often we limit them to glorified word problems or a collection of worksheets, usually within the walls of a single, subject-specific classroom.

Head Knowledge and Heart Knowledge

We decided to shift that paradigm by setting aside two weeks in January as a "mini-mester" designed to provide students with immersive experiences that required them to use the design thinking process to solve messy, real-world problems. During this time, we ditched our regular schedule and designated grade-level teams of four or five students each who would work together all day. Each teacher served as a mentor for no more than six teams.

Students were first provided a series of challenges that allowed them to become familiar with the design thinking process and how it works. During this time, they learned ways to effectively define a problem, have empathy for those facing the problem (the user), develop prototypes of solutions, and work through multiple iterations of the prototypes driven by user feedback on their designs until the best idea ultimately emerged. These challenges included topics such as redesigning the school's cafeteria experience and creating prototypes of The Perfect Classroom. Learning the process through these challenges prepared students for addressing the tougher, more complex problem that came next: designing solutions for poverty.

To accomplish this task, students needed to develop a deep understanding of the issue that comes from both "head knowledge" and "heart knowledge." This required them not only to conduct traditional research of poverty-related topics (accessible resources, transportation, food deserts, homelessness, educational attainment, etc.), but also to learn directly from those whose lives had been effected by one or more of these problems. Therefore, we brought in speakers from local service agencies, journalists who cover the plight of the homeless, and those who have personally experienced homelessness or extreme poverty. Empathy develops through listening to real stories by real people.

Motivated by what they had learned and empowered by the belief that they could make a difference, our students decided to tackle the issue of homelessness by constructing a dwelling from reclaimed shipping pallets as a model for transitional housing. Along with building the house, each team also created a plan for an entire transitional housing community, based on precedent studies of other successful communities of this type nationwide.

Once completed, all plans were submitted to a local development group that is designing a mixed-income community for our city. This team volunteered to review our students' work, judge the strength of each design, and provide feedback on each plan. In the end, they identified a sixth-grade team as having the strongest overall plan, stating that it was the most viable, practical model and contained a combination of elements that are frequently found in successful transitional housing communities nationwide. They were amazed that all of this work had been accomplished by children.

The Learning Potential

At the end of our two-week design challenge, one of our new sixth-grade parents approached me to discuss her son's work. "What kind of crazy school sends your kid home excited about what he's learning and believing that he can change the world?" I waited. She smiled and said, "The kind of school that I'm thrilled to have my kid attend."

Two weeks. That's it. Through tapping into the learning potential of design thinking, our students received more education in those two weeks than they ever would have in a "sit-and-get" classroom.

What could you do with two weeks? Imagine what could happen in your school. Imagine the impact you could make if you broke the mold, made the time, and empowered kids to believe and know that they can change the world.